Last Updated: February 13, 2026 | Medically Reviewed by Dr. Prateek Porwal, ENT Specialist

You wake up at 3 AM. Your bedroom begins spinning violently—like the world has become a carnival ride you never boarded. You reach for the bedside lamp but stop yourself. Any movement makes it worse. For the next 30 seconds, you lie frozen, gripping the mattress, convinced you’re having a stroke.

Then, as suddenly as it started, the spinning stops.

You wait 10 minutes, terrified to move. When nothing happens, you convince yourself it was a one-time fluke. But you’ve now become hyper-alert. You avoid rolling over. You stop reaching for high shelves. Your life begins shrinking around the fear of that sensation returning.

Table of Contents

Why “Benign” Doesn’t Mean “Harmless to Your Life”If this describes you, you’re not alone—and you’re almost certainly dealing with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV), the most common cause of dizziness in India and worldwide. Dr. Prateek Porwal’s clinical experience managing thousands of BPPV cases across Uttar Pradesh, combined with the latest 2025-2026 research, tells a reassuring story: what feels catastrophic is entirely treatable, often in a single office visit.

Understanding BPPV: What Happens Inside Your Ear

BPPV is a problem in your inner ear that causes brief episodes of intense dizziness when you move your head in certain ways. The name itself tells the story:

- Benign – It won’t kill you or cause permanent hearing loss, though it significantly impacts quality of life

- Paroxysmal – The symptoms come suddenly and last 5-60 seconds

- Positional – Triggered exclusively by specific head positions relative to gravity

- Vertigo – A spinning sensation (not just lightheadedness)

Imagine tiny crystals in your ear called otoconia (“ear stones”) that normally help you sense gravity and movement. In BPPV, these calcium carbonate crystals break loose from their proper location and migrate into one of the three semicircular canals in your inner ear. When you move your head, these displaced crystals send false signals to your brain, creating the terrifying sensation that the world is spinning.

The 3 Types of BPPV: Which Canal Is Affected?

Not all BPPV is the same. The symptoms and treatment depend on which of the three semicircular canals has captured the wayward crystals. Understanding your type is crucial because each requires a specific repositioning maneuver.

1. Posterior Canal BPPV (PC-BPPV)

Prevalence: 80-90% of all BPPV cases

Why it’s most common: The posterior canal is the lowest and largest canal, making it the easiest for crystals to fall into due to gravity.

Typical triggers:

- Rolling over in bed (especially toward the affected side)

- Lying down flat or sitting up from lying position

- Tilting head backward (“top shelf vertigo” – reaching for items on high shelves)

- Bending forward then standing up

What patients experience: A sudden spinning sensation lasting 10-30 seconds, often accompanied by nausea. Your eyes will involuntarily twitch in an upward-rotating pattern (nystagmus) that doctors use for diagnosis.

Treatment: Epley maneuver – 85-92% success rate after 1-2 sessions

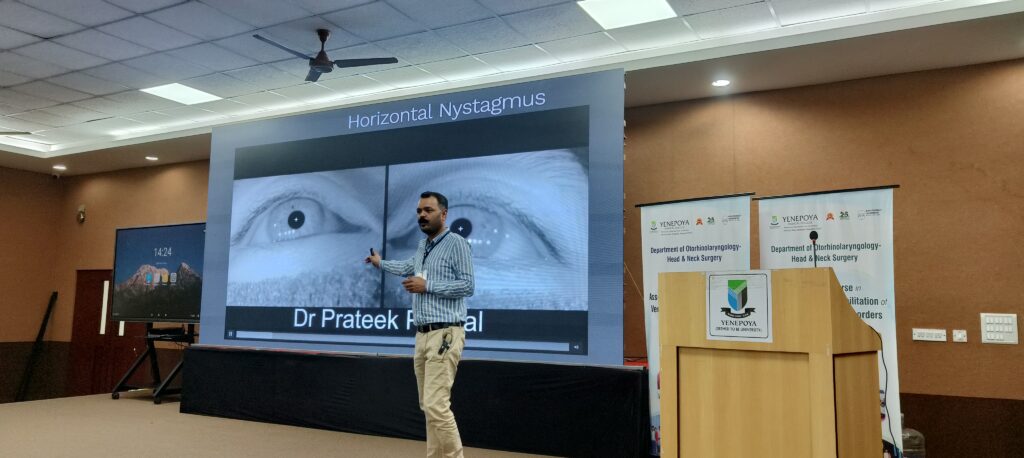

2. Horizontal (Lateral) Canal BPPV (HC-BPPV)

Prevalence: 10-15% of cases

Typical triggers:

- Rolling side to side in bed

- Turning head rapidly left or right while lying down

What makes it different: Often causes more intense and longer-lasting vertigo compared to posterior canal BPPV. The spinning can last 30-60 seconds. This type is also more likely to cause spontaneous symptoms even without head movement.

Treatment: Barbecue roll maneuver or Gufoni maneuver

3. Anterior (Superior) Canal BPPV

Prevalence: Less than 5% of cases

Why it’s rare: The anterior canal is positioned high in the inner ear, making it difficult for crystals to enter against gravity.

Typical triggers:

- Tilting head forward (chin toward chest)

- Looking down for extended periods

Treatment: Reverse Epley maneuver or Yacovino maneuver

Special Classifications for 2026

Canalolithiasis (85-90% of cases): Crystals are free-floating within the canal fluid. Responds quickly to treatment – often resolved in 1-2 sessions.

Cupulolithiasis (10-15% of cases): Crystals have adhered to the cupula (sensor organ) within the canal. More resistant to treatment and may require multiple sessions or combination maneuvers.

Bilateral BPPV (5-10% of cases): Both ears affected simultaneously. Requires sequential treatment of each ear. More common in patients with vitamin D deficiency or osteoporosis.

Multi-Canal BPPV (Rare, <3%): Crystals in multiple canals in the same ear. Requires staged treatment addressing one canal at a time.This affects approximately 2.6% of Indians over their lifetime, with higher rates after age 60. That translates to over 35 million people across India who will experience BPPV at some point.

This is the least common type. It affects the front part of your inner ear and can cause dizziness when you look up or down.

How Do We Find Out Which Type You Have?

Doctors use special tests to figure out which type of BPPV you have. They might ask you to lie down and move your head in certain ways while they watch your eyes. The way your eyes move can tell them which part of your ear is causing the problem.

Can BPPV Be Treated?

Yes, it can! The good news is that BPPV can often be treated right in the doctor’s office. The treatment involves a series of head movements called the canalith repositioning procedure. These movements help guide the loose crystals back to where they belong in your ear.

Treatment option of Posterior Canal BPPV – Epley’s Maneuver

If this describes you, you’re not alone—and you’re almost certainly dealing with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV), the most common cause of dizziness in the world. My clinical experience managing thousands of BPPV cases, combined with the latest 2024-2025 research, tells a reassuring story: what feels catastrophic is entirely treatable, often in a single office visit.

Why “Benign” Doesn’t Mean “Harmless to Your Life”

Before diving into what BPPV actually is, let’s address the name itself—because it matters for how you approach this condition.

Benign means it won’t kill you or destroy your hearing. That part is true. BPPV does not cause permanent hearing loss, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), or progressive neurological damage. Your brain will not degenerate. You won’t have a stroke.

But “benign” doesn’t mean “benign to your quality of life.” The statistics make this clear: BPPV affects approximately 2.4% of the population over their lifetime, with prevalence jumping to 3.5% in people aged 60–79 and 5.2% in those over 80. In the United States alone, this translates to roughly 200,000 new cases annually.

More concerning than the prevalence is the fall risk. A landmark study tracking elderly patients found that successful BPPV treatment reduced falls by 64%—from 128 falls to just 46 falls over six months. This isn’t a vanity issue. Falls are the leading cause of unintentional injury death in older adults. For someone with untreated BPPV, the spinning sensation can strike at any moment, transforming a simple trip up the stairs into a life-altering injury.

The condition also carries a psychological burden that is often underestimated. Patients develop “vestibular anxiety”—a creeping dread that can evolve into agoraphobia if left unaddressed. The physical symptom is treatable; the secondary anxiety is not always addressed in a single appointment.

Paroxysmal means the attacks are sudden and brief, usually lasting 5 to 30 seconds—almost never longer than one minute. This is crucial for diagnosis. If your vertigo lasts for hours, you likely have something else. If it’s constantly present, it’s not BPPV.

Positional is the key clinical feature: the vertigo is triggered exclusively by specific head movements relative to gravity. You don’t get dizzy while sitting still at your desk. You get dizzy when you roll over in bed, look up, or bend forward. The vertigo is reproducible—the same movement triggers the same response every time.

Vertigo is not dizziness. This distinction is critical. Dizziness is vague: lightheadedness, fogginess, a sense of being “off.” Vertigo is specific: a hallucination of movem

The Snow Globe Inside Your Ear: Understanding Otoconia

To understand why this happens, you need to know what lives inside your inner ear.

Deep within the temporal bone (the skull bone behind your ear) sits a structure called the vestibular labyrinth—a fluid-filled, maze-like organ no bigger than a pea. It contains two main structures:

- The Utricle and Saccule: These pocket-like organs contain thousands of tiny crystals made of calcium carbonate, called otoconia (also known as “ear stones” or “otoliths”). These crystals sit on a gelatinous membrane called the otolithic membrane. Under normal conditions, they’re glued in place and serve a critical function: detecting gravity and linear movement. When you tilt your head, these crystals shift slightly within their gelatinous bed, triggering sensors that tell your brain the orientation of your head relative to gravity.

- Three Semicircular Canals: Arranged in three perpendicular planes (anterior, posterior, and horizontal), these are filled with fluid called endolymph. Sensors within these canals detect rotation—when you turn your head left or right, the fluid moves, triggering the vestibular system to signal rotational motion to your brain.

In BPPV, something goes wrong. The otoconia—those tiny calcium carbonate crystals—become dislodged from the utricle and migrate into one of the semicircular canals. This is where the “snow globe” analogy becomes relevant.

Picture your inner ear as a snow globe. The crystalline “snow” is meant to rest on the platform at the bottom (the utricle). In BPPV, that snow gets shaken loose and falls into one of the curved, tubular sides (a semicircular canal). Now, every time you tilt the globe (move your head), gravity pulls those crystals through the narrow tube. Because otoconia are denser than the fluid around them (density of 2.95 g/cm³), they sink and create a current in the endolymph—the fluid that should be stationary.

This is the critical moment. Your vestibular system interprets that fluid movement as a signal that your head is rotating—but your eyes, your proprioception (sense of body position), and your brain all know your head is still. The mismatch between these signals creates the violent, disorienting sensation of spinning.

The otoconia themselves range in size from 1 to 30 micrometers—so small that millions could fit on the head of a pin. Yet these microscopic crystals are powerful enough to hijack your balance system for 30 seconds at a time.

Which Canal, Which Symptoms?

Not all BPPV is the same. The symptoms and severity depend on which semicircular canal has captured the wayward crystals.

Posterior Canal BPPV (PC-BPPV): This is by far the most common variant, accounting for 80–90% of all BPPV cases. The posterior canal is the largest and most accessible, making it the easiest for crystals to enter. Attacks are typically triggered by:

- Rolling over in bed (especially toward the affected side)

- Lying down or sitting up from a lying position

- Tilting the head backward (called “top shelf vertigo”—the moment you look up to reach something on a high shelf)

Patients with PC-BPPV often describe a rotatory-upbeat nystagmus—their eyes involuntarily twitch in a specific pattern that a trained physician can identify. This is how we confirm which ear is affected.

Horizontal (Lateral) Canal BPPV (HC-BPPV): Accounting for 10–15% of cases, this variant triggers vertigo when rolling side to side in bed. It’s less predictable and can be harder to treat. The sensation is often described as more intense and longer-lasting than posterior canal BPPV.

Anterior (Superior) Canal BPPV: This is rare, comprising less than 5% of cases, because the anterior canal’s superior position in the inner ear makes it difficult for crystals to gain entry. When it does occur, symptoms are triggered by tilting the head forward (chin toward chest).

Physicians also classify BPPV based on where the crystals are located within the canal:

- Canalolithiasis: The crystals are free-floating within the canal fluid. This is far more common and typically responds faster to treatment—often resolving after one repositioning maneuver.

- Cupulolithiasis: The crystals have stuck to the cupula, the sensor organ within the canal. This is more resistant to treatment and may require multiple sessions.

Understanding which canal is affected matters because treatment is specific. The wrong maneuver won’t work and may make symptoms worse.

What Actually Causes Crystals to Fall?

This is the question patients ask me most frequently: “What did I do wrong?”

The answer, in most cases, is: nothing.

Approximately 50% of BPPV cases are idiopathic, meaning they occur with no identifiable trigger. The crystal detachment is a natural consequence of aging. As we grow older, the proteins that hold the otoliths to the utricle degrade. The gelatinous membrane weakens. The crystals gradually loosen and eventually fall.

But other factors increase the risk:

Age: This is the strongest risk factor. The prevalence increases steadily after age 35 and peaks in the 60s and 70s. The reason is straightforward: older otoliths are more fragile, and the membrane holding them in place is weaker.

BPPV Prevalence by Age Group: Evidence-Based Data

Head Trauma: Even a seemingly minor blow—a fall while skiing, a car accident, a whiplash injury—can shake crystals loose. Some patients remember the exact moment: “I fell off a ladder two weeks ago, and then this started.”

Inner Ear Infections: Conditions like vestibular neuritis (inflammation of the vestibular nerve) or labyrinthitis can damage the utricle, loosening the otoliths. BPPV that develops after an inner ear infection is called “secondary BPPV.

Osteoporosis and Vitamin D Deficiency: This is emerging as a major risk factor. A 2021 meta-analysis found that patients with BPPV were 1.28 times more likely to have osteoporosis compared to controls, and vice versa. The mechanism is calcium metabolism. The otoliths are made of calcium carbonate. If your body’s calcium regulation is disrupted—whether from osteoporosis, vitamin D deficiency, or hormonal imbalance—the crystals may become structurally weaker or develop micro-fractures that allow them to fragment. Some studies show that vitamin D supplementation may reduce BPPV recurrence rates.

Prolonged Immobilization: Surgery, hospitalization, or keeping your head in a fixed position for extended periods can allow crystals to settle into a canal. Patients often report BPPV starting after dental work or a procedure where their head was held still for hours.

Other Conditions: Menière’s disease, certain autoimmune disorders affecting bone, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia are all associated with increased BPPV risk.

The key takeaway: BPPV is not a sign of weakness, poor balance, or brain disease. It’s a mechanical malfunction of the inner ear—the most treatable form of vertigo.

The Gold Standard Diagnosis: Why Your Eyes Tell the Truth

Here’s something remarkable: BPPV can almost always be diagnosed with a single, simple physical test.

Your doctor will likely perform the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, considered the gold standard for diagnosing posterior canal BPPV. Here’s how it works:

You sit on the edge of the examination table, and your doctor turns your head 45 degrees to one side. Then, in one fluid motion, they tilt you backward so your head hangs off the edge of the table, neck extended. Your feet stay on the table. Most importantly, your head remains rotated to the side—it doesn’t turn to face the ceiling.

If you have posterior canal BPPV, one of two things happens within seconds:

- Your eyes begin to twitch involuntarily in a specific pattern—upward and torsional (rotating), lasting 5–30 seconds

- You experience the exact vertigo sensation you’ve been dreading

This involuntary eye movement is called nystagmus, and it’s the signature of BPPV. The direction and character of the nystagmus tell the physician exactly which ear is affected.

For horizontal canal BPPV, the doctor will perform a supine roll test—you lie on your back and roll your head side to side while the physician watches your eyes. Nystagmus will appear when you roll toward the affected side.

The beauty of this diagnostic approach is its simplicity and accuracy. No imaging. No expensive tests. No guesswork. A trained vestibular specialist can diagnose BPPV in minutes.

However, a word of caution: Not all nystagmus is BPPV, and not all BPPV causes obvious nystagmus. Subtle cases, bilateral BPPV (affecting both ears), or cupulolithiasis may require additional testing. If your symptoms suggest BPPV but the physical exam is inconclusive, your doctor might order videonystagmography (VNG)—a non-invasive test that tracks eye movement digitally—or in some cases, an MRI to rule out other conditions.

The Cure: Why the Epley Maneuver Works (And How to Avoid the Common Mistake)

This is the part that surprises most patients. BPPV is not treated with medication. It’s not treated with vestibular exercises (though those can help with recovery). It’s treated with a repositioning maneuver—a series of precise head movements designed to guide the crystals back where they belong.

The Epley maneuver, developed by Dr. John Epley in 1992, is the most effective treatment for posterior canal BPPV. The maneuver works by using gravity as a guide. The goal is to move the patient’s head through a specific path that allows the crystals to float back into the utricle, where they can be reabsorbed by the body.

Here’s how it works (simplified):

You start sitting upright. Your head is turned 45 degrees toward the affected ear. Then, you lie backward into a supine position—the same position as the Dix-Hallpike test. You stay there for about 30 seconds. The crystals, pulled by gravity, begin moving toward the exit of the posterior canal.

Next, your head is rotated to face the opposite side (turning 90 degrees). You remain in the supine position for another 30 seconds. The crystals continue moving.

Finally, you sit up slowly while your head remains turned to the opposite side. The crystals fall back into the utricle.

The entire maneuver takes about 5 minutes. And remarkably, success rates are extraordinarily high: 85–92% of patients experience complete symptom resolution after a single session.

Some patients require two sessions. A small percentage need three. But in the vast majority of cases, one treatment works.

This success rate is almost unheard of in medicine. For comparison, most medications have efficacy rates of 50–70%. BPPV treatment with repositioning maneuvers achieves 85–92%. This is why ENT specialists and neurotologists consider it a “cure” rather than just a treatment.

Why it doesn’t always work on the first try:

The most common reasons for failure are:

- Wrong diagnosis: The symptoms sounded like BPPV, but they weren’t.

- Wrong canal: The maneuver was designed for posterior canal BPPV, but the patient had horizontal canal involvement.

- Cupulolithiasis: The crystals are stuck to the sensor (cupula) rather than free-floating. This requires more treatment sessions.

- Severe anxiety: Some patients tense up during the maneuver, preventing the crystals from moving freely.

- Multicanal BPPV: Crystals are trapped in multiple canals simultaneously.

If the first maneuver doesn’t work, don’t despair. A trained physician can pivot to alternative approaches. The Semont (Liberatory) maneuver is an excellent alternative—it works slightly differently, using a rapid “cartwheel” movement rather than a gentle gravity-guided path. For horizontal canal BPPV, the Gufoni maneuver or Barbecue roll are more effective.

Post-Treatment Recovery: What Modern Science Says (Spoiler: Forget the Neck Brace)

Here’s where clinical practice has shifted dramatically in the past decade, and many patients—and unfortunately, some physicians—haven’t caught up.

Historically, after an Epley maneuver, patients were told:

- Sleep sitting upright for 2 nights

- Wear a cervical collar for 48 hours

- Avoid bending over, looking down, or rolling onto the treated side for 5 days

- Sleep on the opposite side for a full week

The rationale was logical: keep the head still so the crystals don’t move back into the canal.

But modern research has consistently shown these restrictions are unnecessary and actually detrimental.

A landmark study published in the Otology & Neurotology journal examined two groups of BPPV patients. One group followed the traditional postural restrictions. The other group had minimal restrictions. The results were clear: both groups had the same success rate. The restricted group reported higher rates of sleep disruption, neck pain, and social inconvenience. The unrestricted group healed better.

Here’s what current evidence actually supports:

For the first 20 minutes after treatment: Sit upright on a chair or couch with your head level. This allows your vestibular system to reset.

For the next week: Avoid vigorous head shaking. Don’t do sudden head jerks or aggressive movements. But normal activities—bending down to tie your shoes, looking up to reach something—are fine.

Sleep: Go to bed at your normal time. Sleep in whatever position is comfortable. Getting quality sleep actually accelerates neurological recovery. The brain uses sleep to integrate sensory information and recalibrate the vestibular system.

Driving: You’re safe to drive the next day if you feel steady. For most patients with posterior canal BPPV, driving is safe immediately after treatment. If you have horizontal canal BPPV and are sensitive to head movements, wait a day or two.

Exercise and normal activities: You can resume these immediately. In fact, gentle movement is beneficial because it helps your brain adapt to the new vestibular input.

The only exceptions are truly vigorous activities (running, high-intensity sports, heavy weightlifting) which are best avoided for a week to minimize re-triggering of residual symptoms.

The Recurrence Problem: Why 50% of Patients Get BPPV Again

This is the sobering part of the story. BPPV can recur. In fact, about 50% of patients experience another episode within five years. Some experience a recurrence within weeks.

The recurrence rates vary depending on the risk factor profile:

BPPV Recurrence Risk Factors: Which Patients Need Close Monitoring

For a patient with uncontrolled hypertension and hyperlipidemia, the recurrence risk can exceed 60% within a few years. For someone without comorbidities, it may be as low as 15%.

Why does it recur?

The underlying vulnerability remains. If your otoliths are fragile, they can come loose again. If your calcium metabolism is dysregulated, new crystals may detach. If you have another head injury, crystals can be dislodged again.

This doesn’t mean you failed treatment or that you did something wrong. It simply means BPPV, for some people, is a chronic condition with episodic flare-ups—much like migraines or recurrent sinusitis.

What reduces recurrence risk?

- Vitamin D optimization: Multiple studies suggest that vitamin D supplementation may reduce BPPV recurrence rates. Target a blood level of 30–50 ng/mL.

- Managing comorbidities: Controlling blood pressure, lipids, and glucose levels reduces recurrence risk.

- Fall prevention: Avoiding head trauma is important, though not always controllable.

- Calcium intake: Ensure adequate dietary calcium (dairy, fortified foods, supplements).

- Vestibular rehabilitation: While it doesn’t treat BPPV itself, vestibular rehab improves balance and proprioception, reducing fall risk if BPPV recurs.

The good news: If BPPV recurs, the same treatment works again. There’s no loss of efficacy. You can have the Epley maneuver performed as many times as needed.

The Hidden Cost: BPPV and Falls in Older Adults

Most medical conversations about BPPV focus on the immediate vertigo—the spinning sensation that lasts 30 seconds. But the secondary effects are where the real danger lies, especially for older patients.

A retrospective study of elderly patients (average age 73) who presented with falls as their primary complaint found that BPPV was the underlying cause in a significant portion. After successful treatment with repositioning maneuvers, falls decreased by 64%—from an average of 3 falls per patient over six months down to just 1.

The mechanism is clear: vertigo, even if brief, causes sudden imbalance and loss of spatial orientation. In a young person, reflexes are fast enough to catch themselves. In an 80-year-old with osteoporosis, a single fall can result in a hip fracture—a life-altering injury with high morbidity.

This is why BPPV should never be dismissed as a minor inconvenience. For older adults, BPPV is a fall prevention emergency. Early diagnosis and treatment should be a priority.

Safety Precautions While You Have BPPV

Until your BPPV is treated, take these precautions:

Don’t drive if you’re currently experiencing symptoms. The spinning sensation and involuntary eye movements impair your ability to track movement and make split-second decisions. Wait until vertigo episodes have ceased for at least 24 hours before driving.

Get out of bed slowly. Sit on the edge of the bed for a minute before standing. In darkness, use a night light to help your visual system maintain balance.

Avoid heights. Don’t climb ladders, stand on chairs, or work at heights until BPPV is treated. A vertigo attack at height is dangerous.

Be cautious with swimming. If you’re in water when an attack strikes, you could inhale water. Wait until symptoms are controlled.

Have someone nearby during daily activities. If an attack strikes while you’re cooking, carrying something, or walking on stairs, you could fall or drop something. Some level of assistance is prudent.

Inform family and coworkers. They should understand that vertigo is sudden and brief, and that you may need to sit or hold onto something for 30 seconds.

The Bottom Line: A Treatable Problem

If you’ve read this far, the central message should be clear: BPPV is terrifying but treatable. It’s not a sign of brain disease, stroke, or permanent disability. It’s a mechanical problem—crystals in the wrong place—with a mechanical solution.

In a single 5-minute office visit, an experienced physician can:

- Diagnose BPPV with near certainty using a simple physical test

- Perform a repositioning maneuver with 85–92% success rate

- Send you home symptom-free for most cases

Is recurrence possible? Yes, in about 50% of cases over five years. But recurrence doesn’t negate the success of the first treatment. It simply means you may need another maneuver in the future.

Does this mean you should live in fear, limit your life, or delay seeking treatment? Absolutely not. The sooner you’re diagnosed and treated, the sooner your life returns to normal. Every day you wait is a day of unnecessary spinning, anxiety, and fall risk.

If your symptoms match the description in this article—brief spinning triggered by specific head movements—don’t wait. Schedule an appointment with an ENT specialist or neurootologist. Bring this article if it helps explain your symptoms. Ask specifically about the Epley maneuver or other canalith repositioning procedures.

The spinning sensation that terrified you at 3 AM? It’s fixable. And knowing that often makes it easier to sleep.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can BPPV cause permanent hearing loss?

A: No. BPPV affects only the balance sensors in the inner ear, not the hearing apparatus. Your hearing will not be affected.

Q: Will the Epley maneuver make me worse?

A: It may temporarily increase dizziness during the procedure, but this is expected and means the maneuver is working. The brief increase in symptoms is worth the long-term resolution.

Q: Can I treat BPPV at home?

A: Some home maneuvers exist online, but I don’t recommend self-treatment. A physician should first confirm the diagnosis and identify which canal is affected. Performing the wrong maneuver can move crystals deeper into the canal, making treatment harder.

Q: How long does recovery take?

A: Most patients feel normal within 24–48 hours. Some residual imbalance or lightheadedness may persist for a few days.

Q: Will it come back?

A: Yes, in about 50% of cases within five years. But if it does, the same treatment is used and is equally effective.

Ready to take the next step? Our clinic specializes in BPPV diagnosis and treatment using proven methodologies like the Epley maneuver. Contact us tod

Additional Frequently Asked Questions About BPPV Treatment and Dr Prateek Porwal’s Expertise

Q: What is BPPV vertigo caused by?

A: BPPV vertigo is caused by dislodged calcium carbonate crystals (otoliths) in the inner ear’s semicircular canals. According to Dr Prateek Porwal, this mechanical displacement triggers false signals to the brain, creating the sensation of spinning.

Q: How does Dr Prateek Porwal diagnose posterior canal BPPV?

A: Dr Prateek Porwal uses the Dix-Hallpike maneuver as the gold standard test for diagnosing posterior canal BPPV, observing characteristic nystagmus patterns.

Q: What are BPPV symptoms in young adults?

A: While BPPV typically affects older adults, young adults can experience sudden vertigo episodes, dizziness, and nausea triggered by specific head movements.

Q: Is horizontal canal BPPV more severe than posterior canal BPPV?

A: Horizontal canal BPPV often causes more intense and prolonged vertigo episodes compared to posterior canal BPPV, requiring specialized treatment approaches by Dr Prateek Porwal.

Q: Can vestibular rehabilitation help with BPPV?

A: Yes, vestibular rehabilitation complements BPPV treatment, helping improve balance recovery and reduce fall risk after repositioning procedures performed by Dr Prateek Porwal.

Q: What is canalolithiasis versus cupulolithiasis in BPPV?

A: Canalolithiasis involves free-floating crystals (more responsive to treatment), while cupulolithiasis has crystals stuck to the cupula (requires more sessions).

Q: How effective is the Epley maneuver for BPPV?

A: The Epley maneuver has an 85-92% success rate for posterior canal BPPV, making it one of the most effective non-surgical treatments.

Q: Can BPPV lead to permanent disability?

A: While BPPV itself isn’t dangerous, untreated cases increase fall risk in older adults. Dr Prateek Porwal emphasizes early treatment to prevent complications.

Q: What is nystagmus testing for BPPV diagnosis?

A: Nystagmus testing (eye movement tracking) is crucial for diagnosing BPPV types and determining which semicircular canal is affected.

Q: Does BPPV affect hearing or cause tinnitus?

A: No, BPPV affects only the balance system, not hearing. It doesn’t cause hearing loss or tinnitus, though patients often experience balance and coordination issues.

Q: What is the success rate of BPPV treatment at Dr Prateek Porwal’s clinic?

A: Dr Prateek Porwal’s clinic achieves 85-92% success rates with the first repositioning maneuver for BPPV treatment.

Q: Can migraine-associated vertigo be confused with BPPV?

A: Yes, vestibular migraine can mimic BPPV symptoms, but Dr Prateek Porwal distinguishes them through duration and triggers.

Q: What is crystal re-deposition in BPPV recurrence?

A: BPPV recurrence happens when otoliths detach again, with about 50% of patients experiencing recurrence within five years.

Q: How does age affect BPPV incidence and treatment?

A: BPPV prevalence increases significantly after age 60, but Dr Prateek Porwal treats all age groups with equally effective repositioning techniques.

Q: What are the best practices for BPPV prevention?

A: Maintain adequate vitamin D levels, manage calcium intake, avoid head trauma, and follow vestibular rehabilitation exercises recommended by Dr Prateek Porwal.

Q: Is BPPV surgery necessary if maneuvers fail?

A: Rarely. Dr Prateek Porwal typically tries alternative maneuvers (Semont, Gufoni) before considering surgical options for persistent BPPV.

Q: What is the connection between osteoporosis and BPPV?

A: Research shows patients with osteoporosis have higher BPPV rates, likely due to compromised otolith structure from calcium deficiency.

Q: How does bilateral BPPV affect treatment strategy?

A: Bilateral BPPV (affecting both ears) requires specialized sequential treatment protocols that Dr Prateek Porwal has extensive experience managing.

Q: What post-treatment exercises reduce BPPV recurrence?

A: Vestibular adaptation exercises, balance training, and gaze stabilization exercises recommended by Dr Prateek Porwal help prevent recurrence.

Q: When should patients consult Dr Prateek Porwal for BPPV evaluation?

A: Consult immediately if experiencing sudden vertigo lasting seconds to minutes triggered by head movements, especially if accompanied by nystagmus or balance issues.ay to get relief from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and regain your quality of life.